This post was written by library volunteer George Wise.

Recent celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kurt Vonnegut confirmed his high place on the list of 20th century American novelists. His early novel Player Piano, published in 1952, has a special place in local history. It is a thinly fictionalized picture of the General Electric Company and its Schenectady Works, drawn from Vonnegut's own experience at that Works as a writer in the GE Public Relations Department.

Though it remains one of the most authentic fictional depictions of a company and its workplace, it is not alone in this regard -- even for Schenectady. Nearly half a century before Vonnegut, another future novelist spent a few years as an employee at the GE Schenectady Works. He later captured that experience in a novel. The author, once worthy of reviews in the New York Times, but today totally forgotten, is named Idwal Jones. The novel, published in 1929, is entitled Steel Chips.

Cover of Steel Chips by Idwal Jones, 1929.

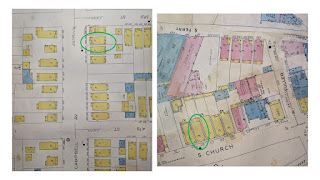

In the mid 1920s, Jones was living in Provence, France. There, in warmth and comfort, he began describing the bitterly cold winter morning on which Steel Chips begins. The protagonist, Bram Dartnell, gets out of bed to prepare to begin his apprenticeship at the Atlas Works. "He threw a dressing gown over his shoulders and went to the window," the description begins, “which the frost had rimmed with white fur. He thawed a spot with his breath, gave it a rub and peered out. Opposite was the yard of the gas works, and under the arc-lamp above the gate figures as rigid as icicles and with coat collars turned up moved past in hurrying silhouettes, then vanished into darkness like spectres. The carbon sputtered and threw capricious gleams and shadows upon the discolored snow. It was an hour before dawn, and Veeder Street was stirring to a realization of coffee and fried bacon and impending duty.”

Are these memories of anticipating the frigid walk down Veeder Avenue and then along the Erie Canal to the main gate of the GE Works? Or are they mere literary imagination?

IWW Union Charter at Schenectady, N.Y., 1906 (Grems-Doolittle Library, Documents Collection)

The actual collision is highlighted in the works of major labor historians such as David Montgomery and Philip Foner. Local historians have explored details and dimensions of the story that even those distinguished scholars missed. What the historians cannot provide is how it looked from the inside, to the people directly involved. Idwal Jones was one of those people.

The history he saw matters. The issues of labor relations, worker representation, and industrial democracy raised just after 1900 at Schenectady resonated down through the 20th century and continue to echo today. They echo when one of today's giant corporations, such as Amazon, faces the same kind of challenge from young upstart unions that the earlier corporate giant, GE, faced from the upstart unions of 1905. The old issues echo today as the IWW, long extinct as a labor union, continues to inspire today's radicals as they protest economic inequality, occupy Wall Street, or take direct action in defense of the environment.

There are clues that in writing his book, Jones was indeed documenting that 1903-1906 episode. In Steel Chips, as in actual Schenectady, the rise of socialism in city politics mixes with the rise of union organization at the city's main manufacturing works. In Steel Chips, as in actual Schenectady, the radical IWW-like union, like the actual Schenectady IWW, has a leadership drawn more from recent immigrants than does the more WASP-dominated, more conservative AFL-like union. In Steel Chips, the unnamed fictional city is visited, during the labor crisis, by a fictional nationally-known radical socialist named Daniel De Tiger, who gives a fiery speech in favor of the radical cause. Real life Schenectady was visited, during that 1903-1906 labor crisis, by an actual nationally-known radical Socialist named Daniel De Leon, who gave a fiery speech in favor of the radical IWW.

In Steel Chips, one main character is a brilliant German immigrant and socialist revered for both his intellect and his character. Readers may be reminded of Schenectady's own Charles Proteus Steinmetz. In one real life biographical sketch, Idwal Jones is described as having been, during his GE days, mechanical assistant to the great engineer Charles Proteus Steinmetz. This is perhaps a later embellishment, but Jones most likely did meet and perhaps talked significantly with Steinmetz.

Charles Steinmetz and a group of GE Schenectady Works employees, circa 1900. (Steinmetz Photograph Collection, Grems-Doolittle Library)

The challenge in using fictional works as historical sources is determining whether the author actually is deliberately trying to inform readers about life as he experienced it, or simply trying to tell a good story. The author of this article had the privilege, many years ago, of asking Kurt Vonnegut himself if Player Piano was intended to depict his actual experience. His answer was, yes, he did write to convey what he experienced at GE, though as a futurist precautionary tale rather than a memoir.

In the case of Idwal Jones, no such direct testimony has yet been found. Certainly many details of the story are not historically accurate. The Steinmetz-like figure is a craftsman, rather than an engineer. The Works Manager of the Atlas Works in Steel Chips is much more abrasive and dictatorial than the actual 1903-1906 GE Schenectady Works manager, the soft spoken and deviously diplomatic George Emmons. The climactic strike described in the book lasts much longer than the actual climactic strike.

Jones' descriptions and character depictions however, have a compelling complexity that transcends the book's clunky plotting and uneven pace. Jones' workers face a convincingly demanding and dangerous work environment, and respond with a credible mixture of grudging acceptance, pride in manual skills, frequent resentment of the foreman's tyranny, and only occasional spontaneous -- and not always heroic -- rebellion. The labor union leaders show solidarity, but not forever. Those fictional union leaders balance their ideals against their family needs. They sometimes reject, but also sometimes accept, job offers that will see them abandoning their coworkers and serving the company as foremen and inspectors. So did such actual GE union leaders of 1900-1910 as Charles Noonan, Harvey Simmons and William Turnbull.

Of course, the fact that details seem convincing does not mean that they are historically authentic. A good writer might just have made them up. The best argument that the details and characters in Steel Chips are historically authentic, an argument made not only by the writer of this article but by a 1920s newspaper reviewer of Steel Chips, is that Idwal Jones does not elsewhere seem to be that good a writer.

Jones himself had a life story. His early writings gained favorable notices from prominent reviewers, such as the famous journalist and literary critic H.L. Mencken. Unlike such literary contemporaries as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Sinclair Lewis, however, Jones's literary star quickly flamed out. He did find a moderately successful West Coast literary niche; producing non fiction works on travel, and pioneering the then new genre of books for wine enthusiasts and foodies. So his writing life turned out satisfying, if not wildly successful.

What about Steel Chips? How did it turn out? Who wins, the radicals, the conservative unionists, or the company? Does the Steinmetz-like character fade away or, like the actual Steinmetz, ascend to urban legend? Does Bram Dartnell go down fighting, head off to California, or settle down and sell out? Sorry, but to find out, you'll have to read the book.

_in_1956.png)